Kids, Data and Privacy: If Your Company’s Not Worried, It Probably Should Be

October 21, 2019Got data? Ask any company and you’ll get an affirmative. But most don’t realize they probably have kids’ data too, and that should be a concern. Knowing what data’s being collected, stored and utilized is critical and it’s not just about having children as customers. “Any company that has family profiles on employee health data, sponsors a “Take Your Child to Work Day,” or has an archive of photos that includes children, has kids’ data,” says privacy expert Kristina Podnar.

Today’s kids have an online identity that begins in infancy via parents, friends and family. By the time they are teens, 95 percent have a smart phone and spend close to half their time online. This raises important questions: What privacy rights should children have? Who will enforce those rights? What should a data protection framework look like? And, what do companies need to know to comply with current laws and mitigate future risk?

This has implications company-wide, stretching from the privacy policy to human resource data to the customer tracking and behavioral information that’s collected for marketing, advertising and sales. Podnar, an international privacy consultant who works with companies from global 1000 brands to small and mid-sized companies, says, “most companies think if they don’t produce a product or service that is for children this doesn’t apply to them,” yet she says it’s been applicable to 100% of her own clients. Podnar finds “organizations don’t realize what data they have and don’t segregate the data, so they can’t differentiate the kids’ data in the pool.”

Jarrod Craik, Vice President of Technology at BlueVenn, concurs saying, “This is a tricky area and a potential minefield for companies. Many don’t quite appreciate that holding children’s data is risky and may become a problem if the data gets into the wrong hands or is used for purposes that were not intended.” There are key questions of whether to keep it, for how long, and whether the benefit is worth the risks involved.

It is also complicated because laws protecting children’s privacy differ. Countries have different age designations regarding who is a child. The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) in the U.S. “requires companies to obtain explicit, verifiable permission from parents before collecting, using or disclosing personal information from children under 13 or targeting them with ads,” according to the New York Times.

GDPR on the other hand, as explained by The Privacy Hub, “doesn’t set a single universally-applicable age. Instead, it gives the Member States the power to choose their preferred nation-wide age of data consent between 13 and 16. Most EU countries (including the UK) set this age at 13. But in Spain, the age is 14 and in The Netherlands, it’s 16.” In other places, South Korea requires parental consent when processing children’s data, Brazil has a law going into effect in 2020, and Australia and India are looking at adding children’s privacy protection regulation.

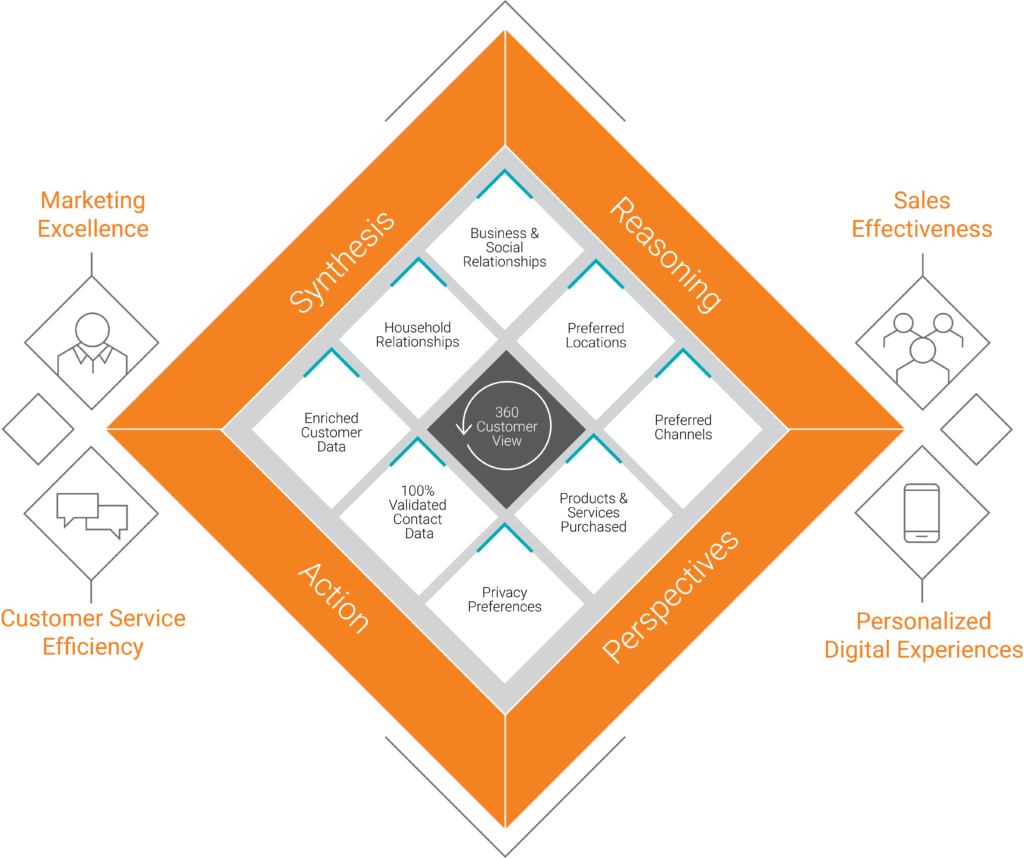

Customer Data Platforms can help significantly by ensuring that company data is unified, consistent and up-to-date. CDPs make it easier to identify what kind of data the organization is holding and whether data is being accessed. In consulting with their clients, Craik says that at BlueVenn, “we’ve always taken the view that holding children’s data is risky, and companies should only hold what has been agreed to and use it just for the stated purpose. It’s good to have a time limit after which you either get rid of the data if you’re not using it, or renew the agreement for a new installment of time. I generally advise taking as little information about children as possible, for example a birthdate to know age, but not gender or other information you don’t need.”

Podnar recommends companies get ahead of the problem now, saying, “if you define guardrails ahead, you won’t have to wonder what data can be used or whether you’ll get in legal trouble”. She says future forward companies are doing this and that “smart marketers are proactively sharing what they’re doing with their customers” as a way to show transparency in their process and instill trust. She believes this will be an increasingly important issue and one that is “ideal for companies to look at while they’re retooling, and before it becomes more heavily regulated,” which Podnar feels certain will come over the next 5 or more years.