Household Marketing: Finding the Decision Maker and Avoiding Blunders

April 30, 2018One of the principles of one-to-one relationship marketing is understanding the individual customer entity that you are interacting with. Defining the customer entity is important not only for the sake of outreach, but also for accurate reporting and analysis.

Nowadays, marketers are putting a stronger emphasis on personalization than ever before. And the simplest form of personalization – using the first name in an email template (i.e. “Hi Rob,”) – might prove tricky or even completely wrong in certain types of businesses.

In financial services businesses, the question of classifying “who the customer is?” is rarely straightforward. Should they consider each individual contact as a customer? Should they group individuals under a single household? This issue may also be relevant for subscription businesses (e.g. does a household need more than one Netflix or Blue Apron account?), for certain retailers such as online supermarkets, and for companies with a B2B business model. These companies may have several contacts for each of their clients, and it’s a common challenge to identify the decision maker within the organization.

You Can Never be Too Insured

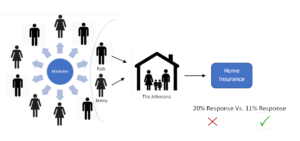

Marketers might prefer a wider outreach within a given household, to increase the exposure of their marketing content to more relevant individuals, thus increasing the probability of response. In financial services, a wider outreach is especially important since the “circle of influence” plays an active role in the decision-making process. According to research conducted by McKinsey & Co., two-thirds of the touch points during the active-evaluation phase involve consumer-driven marketing activities, such as word-of-mouth recommendations from friends and family.

Although the size and shape of the average households has changed throughout the years, households with multiple individuals are still dominant and should be therefore addressed as a whole. According to the latest U.S. Census, households of more than one-person account for more than 70% of all households. Family members, who are participants of this circle of influence, may have a significant role in the financial decision making of the household, especially when it comes to choosing products such as insurance or banking.

The major caveat with this approach begins after the fact, in the assessment and analysis of the marketing campaign.

Here is an example to clarify:

- A marketer at Y.B Insurance Inc. sends out an email to 10 potential prospects.

- Out of these prospects, Rob & Jenny Johnson are married and live in the same house.

- Rob & Jenny decide to request a quote for a home insurance together.

- The marketer at Y.B Insurance Inc. decides to finalize the campaign and analyze the results.

- He sees that 2 out of the 10 prospects responded and requested a quote. A 20% response rate is a great result.

In reality, this 20% response rate figure is misleading since Rob & Jenny are responsible for themselves as a single household, thus – 11% response (1 of 9).

The campaign analysis would potentially be even more skewed if the marketer would have excluded a control group to measure uplift. If Jenny would have been in the test group and Rob in the control group, the results would be completely distorted.

In the example above, the analysis would have produced a 50% response rate for the control group and a 12.5% response rate for the test group.

Targeting a single individual in a household may also prove to be problematic. Who is the decision-maker? Who is the influencer? What if one individual is the primary contact for a life insurance while their spouse is the decision maker for the auto insurance?

Household marketing may also be effective for reducing redundant ad spend. For example, if someone in a household has already purchased a home-insurance policy —then based on the customer database, the marketer should stop presenting home-insurance ads to all individuals in that household. This kind of irrelevant content needs to be taken into special care in these cases, as it might have the negative effect, and influence the decision making in a wrong way.

Group Ahead

Ideally, we would suggest mixing both approaches, to consider the household as the primary entity for reporting and analysis, while communicating with all household participants to maximize the potential effect of the campaign. Here’s how to do it:

The first step will be to create a “single household view” of the data – aggregating different behavioral metrics on a household level (e.g. Total number of accounts – In total and per line of business – Total Spend etc.). The prerequisite of achieving this is to be able to identify the individuals of a household or workers of a company. In financial services, developing the logic for grouping individuals into households is not a simple task. These individuals may have separate accounts which may or may not share the same surname or mailing address. For B2B companies, identifying the individuals of their organizational clients is an easier task, by either requesting the company name as an input or by matching email address suffixes.

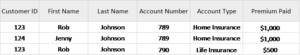

Raw data:

Single Customer View:

Single Household View:

From the illustrations above, you can understand the issue of solely maintaining a single customer view while not referencing a household view (and vice versa in some cases).

The next step would be to create the list of households who should receive the marketing communication, making sure to exclude irrelevant households based on the single household view data (e.g. excluding households with 2 life insurance policies from a life insurance campaign), and break these down to the individuals of each household.

Finally, after the campaign is sent/exposed to the individuals, the response metrics should be aggregated back into the single household view to prepare the campaign analysis.

In Conclusion

Understanding your customer entity is crucial for measuring your marketing efforts on one hand, and for building loyalty and a meaningful relationship with your customers on the other. Different messages might be relevant for specific individuals, while other messages might be holistic and prove to be valuable for the household. For example, transactional emails to renew a subscription or policy should be directed to the primary holder of the account while messaging with a marketing emphasis (such as new offerings, deals or information) will probably relevant for the household as a whole.

Marketers should first reach the awareness that there is a “household” component in their business and customer base and if so strategize their messaging accordingly. Once you know who your audience is, you will be able to measure your success in an accurate manner.